Pandemic 2.0

The cases of human infection with influenza A(H7N9) virus reported in China cannot be called a pandemic. Up to now, there are no signs of human-to-human transmission, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). Nevertheless, there is a pandemic which is actually ongoing; we could call it web pandemic 2.0. And is something that does not come without risks.

The virus on the net

Exactly as it happened during the previous pandemic, in 2009, this event was intensely followed and commented about on the internet, particularly on social media. As evidenced by an hashtag-based search on Twitter (Fig. 1), the informative and emotional content of the tweets related to the H7N9 virus in the period from 2nd to 22nd April may be grouped into five categories (see description below).

NEUTRAL refers mainly to messages aimed to spread information, usually with links to statistics and articles.

ALARM refers to messages that express emotionality and fear.

REASSURANCE refers to messages aimed to hinder possible panic reactions with reassurances and practical advices.

CONSPIRACY refers to messages that hint to conspiracy theories.

DISTRUST refers to messages that express distrust over authorities and experts due to their contrasting information.

Fig. 1

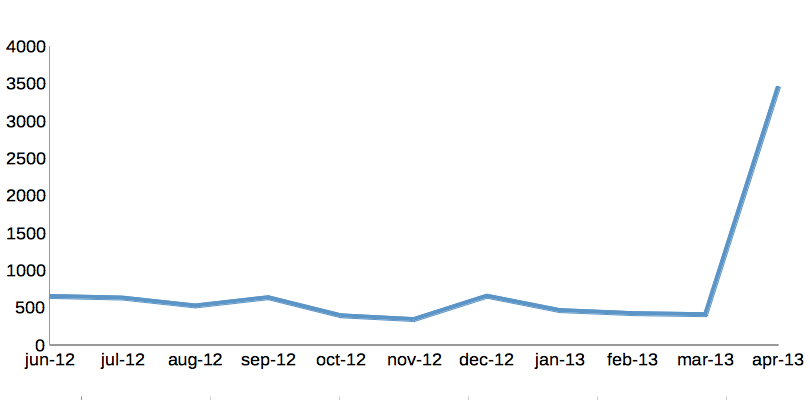

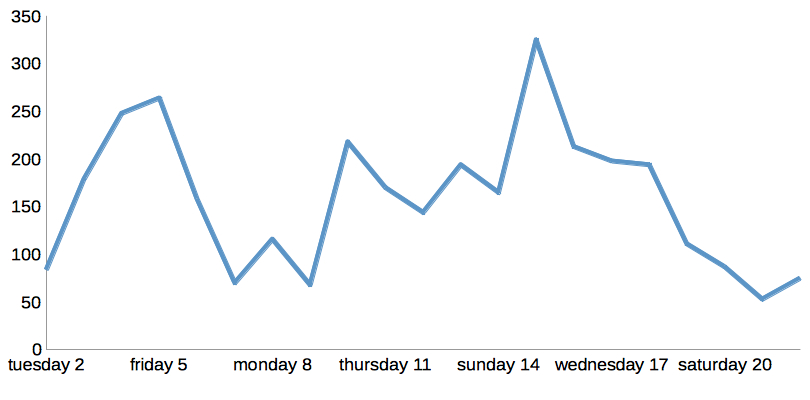

Also, figures 2 and 3 clearly show how the trends of the number of tweets containing the hashtag ‘pandemic’ in the last years and in the last twenty days are related with the spread of the H7N9 virus.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

A lesson from the past

In 2009, a series of communication mistakes from healthcare authorities cost much in terms of trust and reliability, and left the field clear for the suspect that the pandemic was just a machination arranged by pharmaceutical industries to sell more vaccines. A suspect that shattered the credibility of those institutions that are expected to plan efficient preventative measures in case of a real pandemic.

“Now it is important not to ignore the flow of information that runs through the social media and that may influence the population’s behavior and, as a consequence, the course of the pandemic,” declare the experts of TellMe, a consortium of the main research centers around the world dedicated to elaborate new rules for an effective ‘pandemic communication’.

In these days, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the ministers of health from several countries have activated daily online updates on the evolution of the Chinese situation. However, in the very early phase of the outbreak, first tweets from the WHO showed a kind of insistence towards the recommendation of alimentary hygienic measures that are clearly helpful but not strictly inherent to influenza virus transmission. These messages sent when transmission modes were not known yet; until proven otherwise, it was reasonable to think that the H7N9 virus spread like any other influenza virus and no one of them proved to be able to be transmitted through food. A similar misunderstanding already occurred in 2009, when the H1N1 pandemic flu, called the “swine” flu, had a heavy impact on economy due to the drop in sales of pork meat. It is thus necessary to not repeat such a mistake now with the poultry. This does not exclude that raw meat can be contagious by contact or inhalation. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were more cautious and published on their website a document with some recommendations to be followed when travelling to China. Even more caution came from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), whose message was probably the most correct since it admitted that, at the moment, there were very few certainties.

Tweets from the authorities

Despite these early issues, the analysis carried out by the TellMe experts revealed that the authorities seemed to have learnt how to take advantage of the potential of the new technologies. The WHO, for instance, immediately and explicitly chose Twitter as a privileged tool for their update about the number of new cases, thus proving to have understood the significant advantages of this social media in terms of risk communication: 1) it is aimed directly to the reader; 2) the 140 character limit dictates the use of short messages that are more likely to be understood; 3) it helps sharing and disseminate these messages.

This sober kind of communication avoided alarms on the one hand and offered transparency – even when remarking what is still unclear – on the other. In this way, it managed to ward off the accusations of plots and conspiracies that often follow this kind of situations. Until now, those movements that are used to see Big Pharma’s hands behind every move made by healthcare authorities had not so much room on the social network.

The Chinese colonel

In this respect, the voice that gained more media coverage is that of Dai Xu, a colonel of the Chinese air force who is renown in his country for his strong claims. When news of the first cases of infection with the H7N9 virus arose in Shangai, he suggested that such an infection would have been spread in China by the United States. He said that on Weibo, the social network that in China replaced Twitter, which has been banished. This platform played a main role in the very early day of the outbreak, getting through the censorship that firstly tried to take control of the spread of news about the virus. Xu’s claim, reposted by more than 30,000 followers, urged Chinese people to calm down in order not to play into the hands of the Americans who, according to the colonel, already tried to destabilize the Chinese government in 2003 by voluntarily spreading the coronavirus responsible for the SARS.

Internationally, such a suspect has been followed by few other tweets, especially when voices about the new vaccines being prepared with a new technique of synthetic biology developed by Novartis and the Craig Venter Institute. In 2011, US government tested this technique on a virus that was similar to the one now circulating in China; it was named H7N9 too but it was only circulating in birds. «It’s just a coincidence,» declared Robin Robinson, director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). Maybe is just due to the favorable media mood, but it looks like social media trusted him, at least for the moment.

A good start

Finally, the TellMe study concluded that the response from healthcare authorities to the appearance of the new avian flu virus H7N9 in China has been more proper, transparent and adequate than in 2009. “But there is still room for improvement,” insisted the TellMe experts, who also produced a decalogue to sum up the guidelines for an effective communication in case of pandemic. “Communication plans that involve health workers should have been already established, and institutions should have been already active on the main channels – like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube – to report and explain facts also at the national level, to hinder conjectures and exploitations, and at the same time to monitor what is going on in the blogosphere.”

Contacts:

Luca Carra

mobile: 339 8578565

luca.carra2@gmail.com

For further information:

TellMe website: http://www.tellmeproject.eu

TellMe members:

Center for Science, Society and Citizenship, Rome

Haifa University, School of Public Health

Centre in Research for Social Simulation – CRESS, Surrey

National Centre for Epidemiology, Surveillance and health Promotion, CNESPS, Italy

British Medical Journal Group, London

CEDARThree ltd, Bath

European Union of General Practitioners (UEMO)

Latvian center for Human Rights, Latvia

Vrije Universiteit Brussels (VUB)

National Disaster Life Support Foundation (NSLSF), USA

Vitamib (France)

Zadig (Italy)